Pregnancy & the Heart- Will cardiovascular changes affect your training?

Did you know? Some of the first changes that happen to the body when pregnant are cardiovascular!

Long before the belly grows, very specific and targeted changes are happening in the heart and blood vessels. These changes impact the ability to bring nutrients and oxygen to a growing fetus, but they also have a large effect on response to exercise!

To understand what is going on in the pregnant heart, we first have to understand changes to the nervous system. The Autonomic Nervous System is responsible for the involuntary processes in the body- think breathing, digestion, heart rate, blood pressure, etc. During pregnancy, there is an increase in what is called ‘Sympathetic Control’ of this system- this is also called the “fight or flight” response and affects both heart rate and blood pressure. This change in nervous system control, along with the need to increase blood flow to the fetus, are the main causes of the cardiovascular changes seen below (1).

Review of cardiovascular changes in pregnancy- and how to adjust training accordingly:

Heart Rate:

♥ Both resting and exercise heart rate are increased. The exact amount depends on the person, but research shows the increase to be anywhere from 8-20 bpm (2, 3)

♥ Heart Rate Variability (a measure of sympathetic control) is decreased during pregnancy (1). This makes sense, as HRV is a measure of sympathetic control, and lower values correspond to increased ‘stress’ (physical, emotional etc.) levels in the body.

Cardiac Output:

♥ Cardiac Output is a measure of the amount of blood pumped by the heart in a minute. It is dependent on both heart rate and stroke volume (amount of blood pumped per beat).

♥ Both heart rate and stroke volume continue to increase through all trimesters, so cardiac output changes fairly quickly, with a 20% increase in the 1st trimester, and a 40% increase by week 20-28 of pregnancy (2).

Blood Composition:

♥ Blood volume begins to increase around week 7 and continues through the 3rd trimester. Total increase is near 50%. (4)

♥ Volume increase is due to both an increase in Red Blood Cells (18-25% increase) and Plasma (30-50% increase). (4)

Blood Pressure:

♥ Systolic pressure (pressure when heart contracts) increases around 5.6% by full term. (3)

♥ Diastolic pressure (pressure when heart relaxes) initially decreases until 21 weeks, after which it slowly returns to normal. This is due to dilation of blood vessels. (3)

Heart Structure:

♥ Due to an increased workload (higher heart rate and cardiac output) heart muscle increases in size (hypertrophy). This is called ‘reversible hypertrophy’ however, as the maternal heart returns to normal size postpartum. (2)

♥ Heart position in the chest cavity changes- as uterus expands, the heart is pushed upwards and forwards.

Oxygen Consumption (VO2 resting/max):

♥ Increases in blood volume and RBC count also increase the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood. This causes an increase in resting VO2, and may* cause an increase in VO2 max (the maximum amount of oxygen body is able to consume/use). (4,5,6)

♥ * VO2 max is influenced by so many other factors that are also changed during pregnancy (such as ability to exercise, body composition etc), so we cannot say that VO2 max will always increase during pregnancy, however there is a potential for increased VO2 max with increased blood volume.

Something interesting to note is that the changes mentioned above seem to come back to baseline levels fairly quickly postpartum (within 3-6 months) (2). An exception to this may be VO2 max, which some researchers argue could stay higher for longer postpartum (4,5,6).

So what does this mean for exercise?

♥ While pregnant, heart rates and perceived exertion will be higher than normal for a certain level of performance. The amount these variables change depends on the person, and the level of activity they maintain during pregnancy. Interestingly, research studies have found that the increase in HR and decrease in HRV is significantly less in pregnant women who exercise compared to sedentary controls (1).

♥ Recovery times will potentially be longer. Simply put, the body has a lot going on. Low HRV numbers indicate that the body is under much more stress while pregnant, and this will absolutely affect ability to recover from workouts.

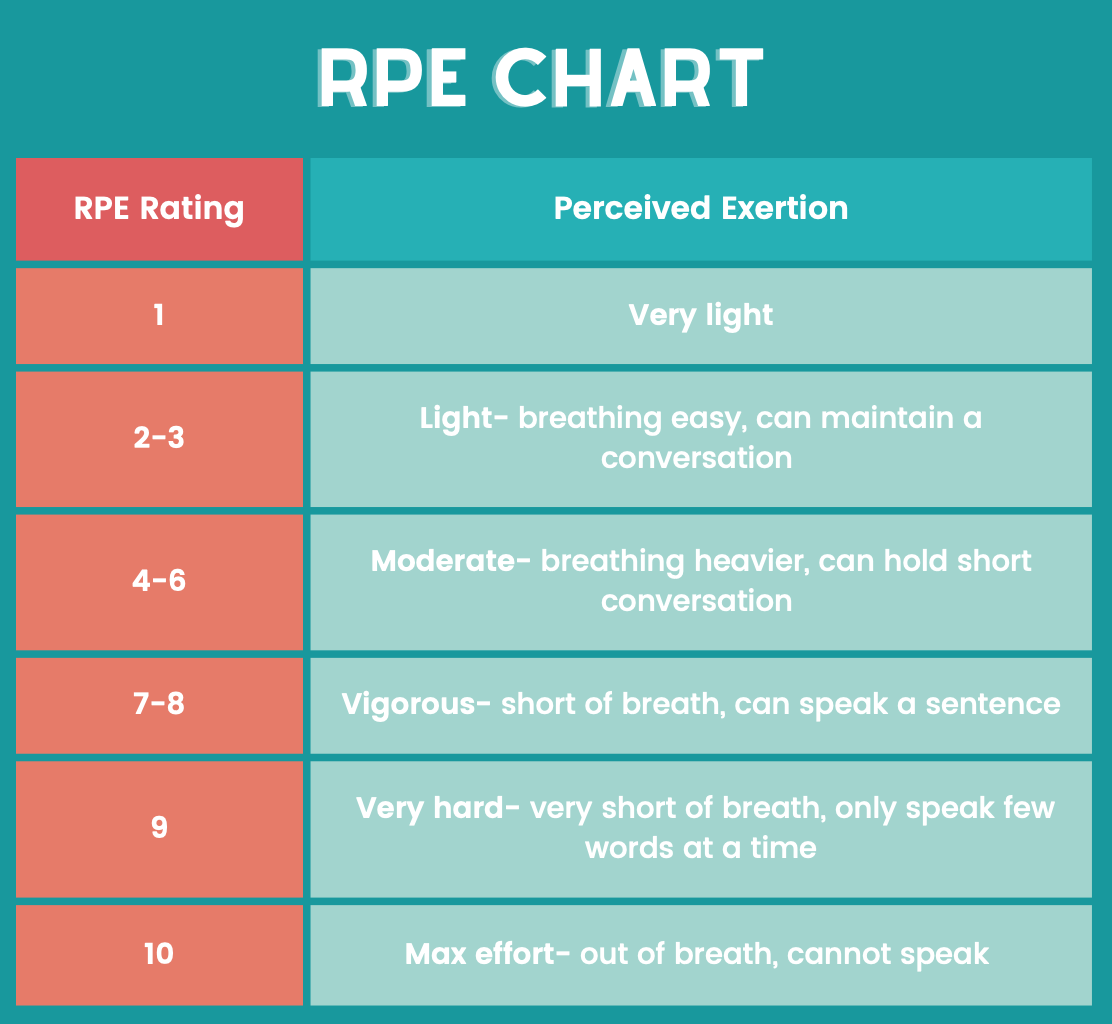

♥ Pregnant training is a great time to utilize an RPE chart (see diagram below). Training by RPE means that performance is determined by how difficult an activity ‘feels’ rather than pace or heart rate. This allows the body to determine its abilities by stress level that particular day- which could be impacted by factors such as prior exercise/recovery, nutrition, sleep, as well as energy devoted to pregnant/fetal growth. RPE charts go from 1-10, with 1 meaning very light exertion and 10 meaning maximal exertion. Low intensity exercise rates 2-3, Medium 4-6, Hard 7-8 and Very Hard 9 on the RPE scale. In application this could mean assigning a pregnant runner longer tempo runs at an RPE of 5, and shorter speed intervals at an RPE of 7.

In regard to maximal intensity exercise- It is important to note that there have been several research studies indicating an abnormal fetal heart rate response (HR outside of 110-160 bpm) when a pregnant woman exercises over 90% of maximum heart rate (7, 8). This abnormal fetal heart rate returned to normal fairly quickly after cessation of exercise (7). While we don’t know for sure that abnormal fetal heart rate is a predictor of fetal distress or future complications (9), it is currently recommended to stay under 90% heart rate max.

For information on estimating your maximum and target heart rate, see article here.

For more information about long distance training (specifically marathon training) while pregnant, see post here and here.

_________________________________________________________________________

References:

- May, L. E., Knowlton, J., Hanson, J., Suminski, R., Paynter, C., Fang, X., & Gustafson, K. M. (2016). Effects of Exercise During Pregnancy on Maternal Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability. PM&R, 8(7), 611–617.

- Savu, O., Jurcuţ, R., Giuşcă, S., van Mieghem, T., Gussi, I., Popescu, B. A., Ginghină, C., Rademakers, F., Deprest, J., & Voigt, J.-U. (2012). Morphological and Functional Adaptation of the Maternal Heart During Pregnancy. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging, 5(3), 289–297.

- Loerup, L., Pullon, R. M., Birks, J., Fleming, S., Mackillop, L. H., Gerry, S., & Watkinson, P. J. (2019). Trends of blood pressure and heart rate in normal pregnancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 167.

- L’Heveder, A., Chan, M., Mitra, A., Kasaven, L., Saso, S., Prior, T., Pollock, N., Dooley, M., Joash, K., & Jones, B. P. (2022). Sports Obstetrics: Implications of Pregnancy in Elite Sportswomen, a Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(17), 4977.

- Treuth, M. S., Butte, N. F., & Puyau, M. (2005). Pregnancy-Related Changes in Physical Activity, Fitness, and Strength: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 37(5), 832–837.

- Clapp, J., & Capeless, E. (1991). The VO2 Max of Recreational Athletes Before and After Pregnancy. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 23(10), 1128–1133.

- Salvesen, K. Å., Hem, E., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2012). Fetal wellbeing may be compromised during strenuous exercise among pregnant elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(4), 279–283.

- Kennelly, M. M., McCaffrey, N., McLoughlin, P., Lyons, S., & McKenna, P. (2002). Fetal heart rate response to strenuous maternal exercise: Not a predictor of fetal distress. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 187(3), 811–816.

- Zavorsky, G. S., & Longo, L. D. (2012). Viewpoint: Are there valid concerns for completing a marathon at 39 weeks of pregnancy? Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(7), 1162–1165.

Aubree McLeod is an ACSM-EP exercise physiologist, researcher in running biomechanics. She has also completed the ICE Preg & PostPartum Course for athletes. She has an M.S. in Exercise Science and has worked in a variety of spaces within the exercise science field including physical therapy, education, research, and run coaching for... Read More